Making the most out of Docker

Some options that might increase performance, some that don’t.

Network

Containers get connected to a bridge network by default.

A software bridge that allows communication between containers running on the same host & bridge.

We can also create and use custom bridges, to create isolated groups of containers.

To allow connections from outside, we must map the host’s ports to a container’s with -p (publish e.g. -p 3306:3306)

This is easy and flexible, but it makes Docker start an additional process (docker-proxy), which can use a non-trivial amount of CPU.

What’s the alternative? Consider using --net=host, which connects the container network directly the host.

In my experience, a considerable boost can be gained, specially when there are multiple connections.

The downside of this is that we run the risk of inadvertently exposing ports to the outside world. Moreover, changing service ports is, yet again, a hassle. We’ll need to deal with configuration settings inside the container.

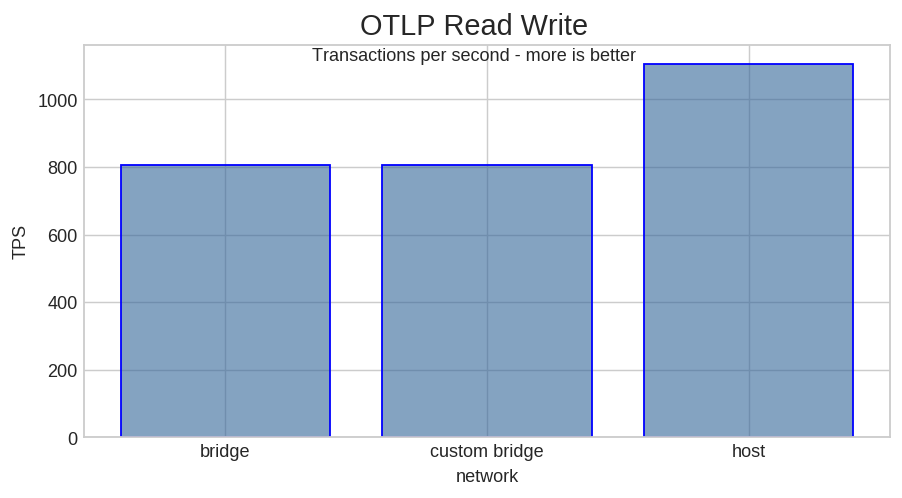

How much more we can get out of Docker? I ran a sysbench OLTP read+write test with 8 threads on MariaDB 10.3.12 to see.

In my test, host network means about a 37% TPS increase. I’ll let you decide if that is worth letting go of port mapping.

Storage

Containers are made up of several layers, the top one is the only one that can be written into. Once a container is stopped and removed, this layer is lost. The layers are managed by one of Docker’s storage drivers, which does copy-on-write. Docker’s documentation states that this feature reduces performance.

To provide permanent storage we can use volumes and bind mounts. Volumes are managed by Docker itself, whereas bind mounts provide a way to map directory or file between the host and the container. In theory, these methods should be more efficient because they bypass Docker’s storage driver.

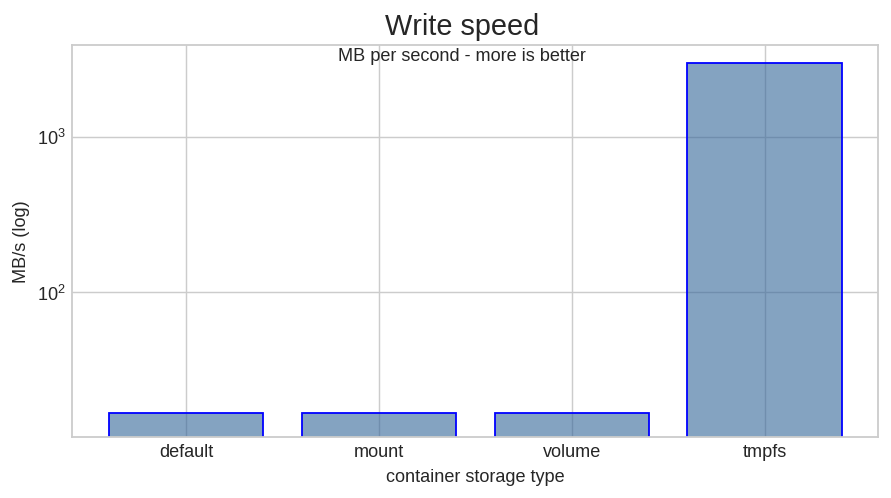

I was curious about a case in which I had to write lots of data but I didn’t need persistence. The best solution would have been to a tmpfs mount, being memory storage, it’s the fastest. But we don’t always have enough memory. What’s the best other alternative?

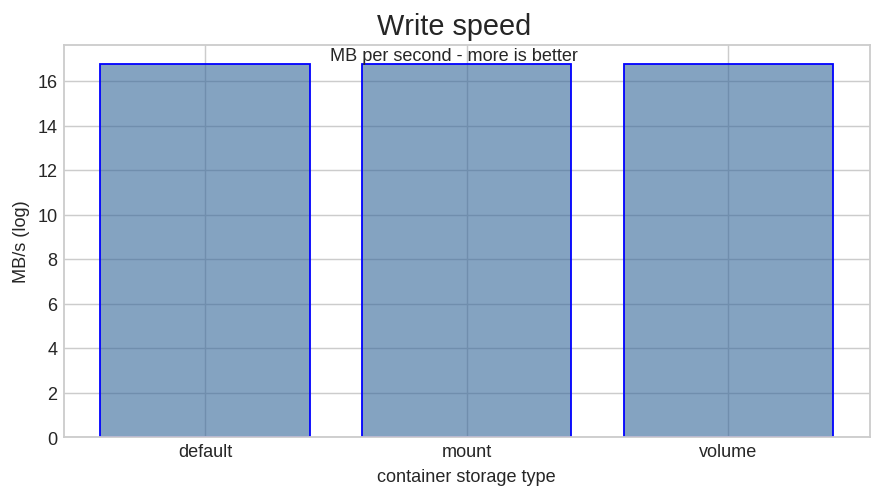

I tested random write speed with fio on an EC2 host with an io1 1000 IOPS volume.

As you can see, the mount option really makes no difference for write speeds.

To put things into perspective I repeated the test with a tmpfs mount. I had to use a log scale to even see the slower options.

Use Limits

Containers, by default, don’t have any limits. Any of them can hoard all the host system’s resources. This may be well and fine for development, but a potential disaster for production.

Thus, a final recommendation: set limits for production containers. At the very least a memory limit. To avoid swapping and containers getting killed by out of memory errors. We can also set limits for CPU and disk I/O.

First, we need to find out suitable limits. We can start the container normally and check resource usage:

docker stats <CONTAINER_ID>

CONTAINER ID NAME CPU % MEM USAGE / LIMIT MEM % NET I/O BLOCK I/O PIDS

529ea41caf55 jolly_borg 3.36% 5.016MiB / 983.9MiB 0.51% 0B / 0B 36.1MB / 24.4GB 7

A lot of details can be found under the /sys/fs/cgroup filesystem. For example, we can get a great deal of interesting memory counters.

-> cat /sys/fs/cgroup/memory/docker/<FULL_CONTAINER_ID>/memory.stats

cache 41623552

rss 1097854976

rss_huge 0

shmem 15343616

mapped_file 24809472

dirty 0

writeback 0

swap 122916864

pgpgin 91463838

pgpgout 91185552

pgfault 165685756

pgmajfault 3525

inactive_anon 373063680

active_anon 738381824

inactive_file 10625024

active_file 15716352

unevictable 0

hierarchical_memory_limit 9223372036854771712

hierarchical_memsw_limit 9223372036854771712

total_cache 41623552

total_rss 1096085504

total_rss_huge 0

total_shmem 15343616

total_mapped_file 24809472

total_dirty 0

total_writeback 0

total_swap 122916864

total_pgpgin 91463838

total_pgpgout 91186010

total_pgfault 165685756

total_pgmajfault 3525

total_inactive_anon 373063680

total_active_anon 738381824

total_inactive_file 10625024

total_active_file 15716352

total_unevictable 0

To get the full container id:

docker ps --no-trunc

Once we have an estimation, we can try starting a new container with some limits.

For a hard memory limit, we can use --memory.

Use --cpus to limit the amount of CPUs available.

When setting a memory limit, Docker will set a swap limit of

--memory* 2. This can be changed with--memory-swap: total swap allowed =--memory---memory-swap.

Container limits can even be changed while they are running.

We don’t need to restart containers as

Docker can change limits at runtime: docker update

# set limits, 4 CPUs, 4G of memory, 1G of swap

docker run -it --cpus=4 --memory=4G --memory-swap=5G ubuntu:latest bash

# increase memory limits, 8G memory, 1G of swap

docker update --memory=8G --memory-swap=9G <CONTAINER_ID>

Related links

- Benchmark data: https://github.com/TomFern/benchmark-data/tree/master/docker-perf-tips

- https://docs.docker.com/network/

- https://docs.docker.com/storage/

- https://docs.docker.com/config/containers/resource%5Fconstraints/

- https://docs.docker.com/config/containers/runmetrics/

See you.

Tomas